Introduction

Built in the period 420-400 BC, the temple of Epicurious Apollo is a great technical achievement of its time, a unique monument, with manneristic features that differentiate it from its contemporary temples and make it a milestone in the history of ancient of Greek architecture, with clear influences recognized in later buildings. Enhancing the charm of the monument, is the fact that it contains architectural elements found in temples dating from all three periods of antiquity (archaic, classical and Hellenistic).

At the same time, the co-existence of many architectural elements of different dates makes it difficult to date the temple with certainty and threatens to precipitate any theory that has been formulated to interpret its multitude of peculiarities. The temple is considered by several scholars to be a pre-Parthenon building, with some parts of it completed at the end of the 5th century. e.g. However, it is certain that in the same place there was a cult sanctuary and a temple of the archaic times.

For Greece, the Temple of Epicurious Apollo was the first monument to be included in 1986 in the list of UNESCO’s world cultural heritage.

The interpretation of the nickname “Epicurius” is given by Pausanias, according to which Apollo, during the Peloponnesian war, helped (healed) the Phigalians to deal with an epidemic disease, a Covid of the time and they to express their gratitude to the god they built the classic temple in Vasses. The archaeologist K. Kourouniotis, during the excavation of the temples on the top of Kotilo, found an inscription in which Apollo is referred to with the epithet Vassitas, formulating the opinion that this was the god’s nickname before 420 BC when he was given the nickname Epicurios.

Iktinos

Type and morphological characteristics of the temple of Bassae

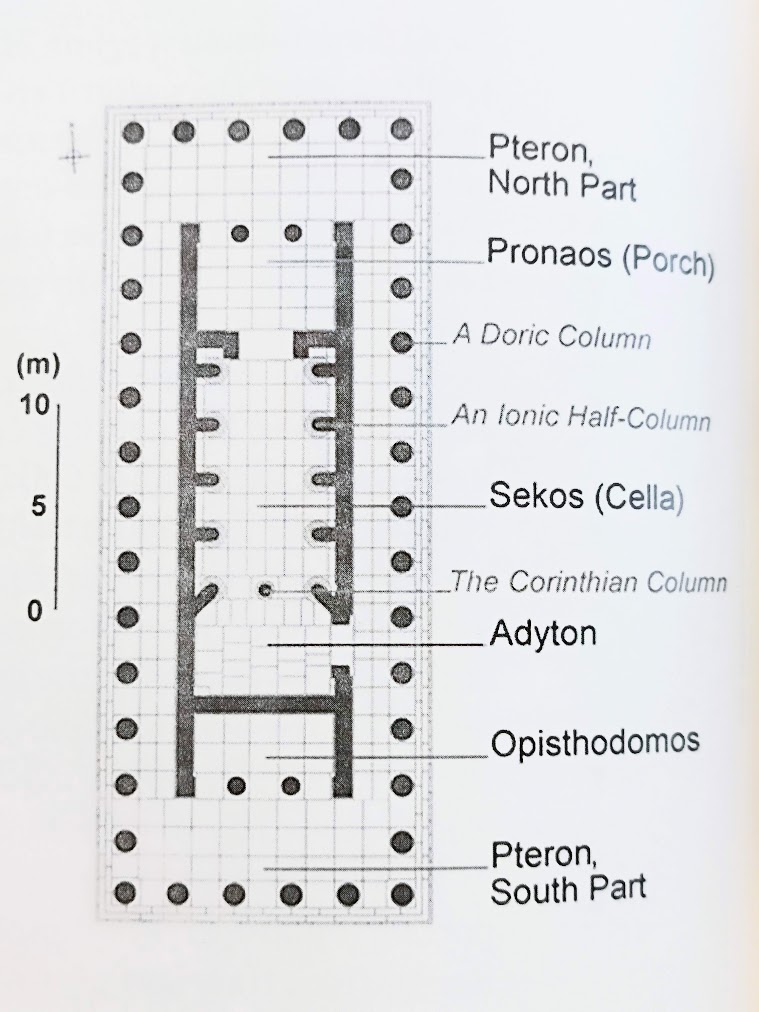

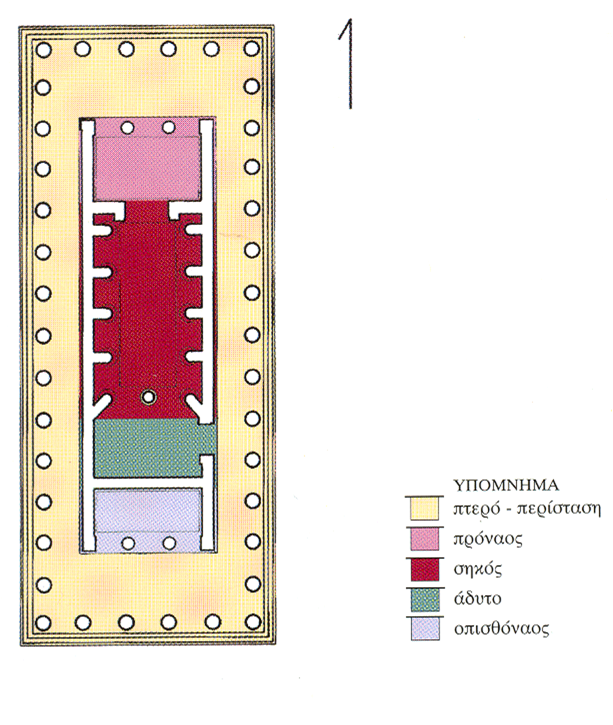

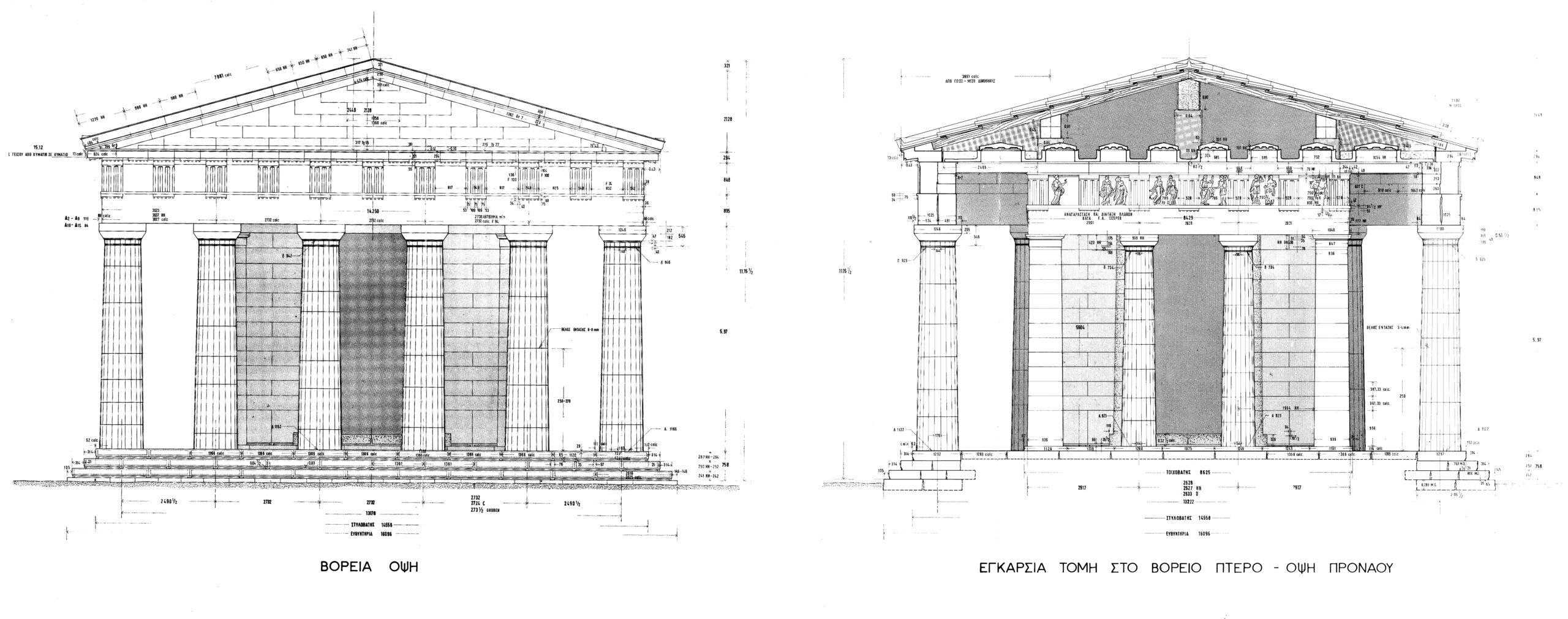

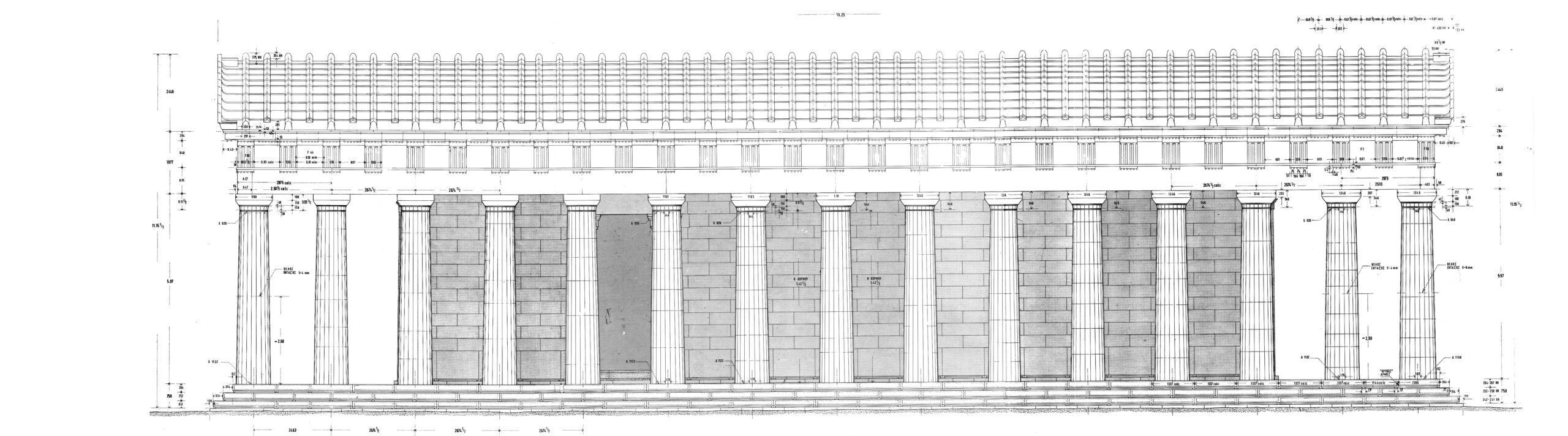

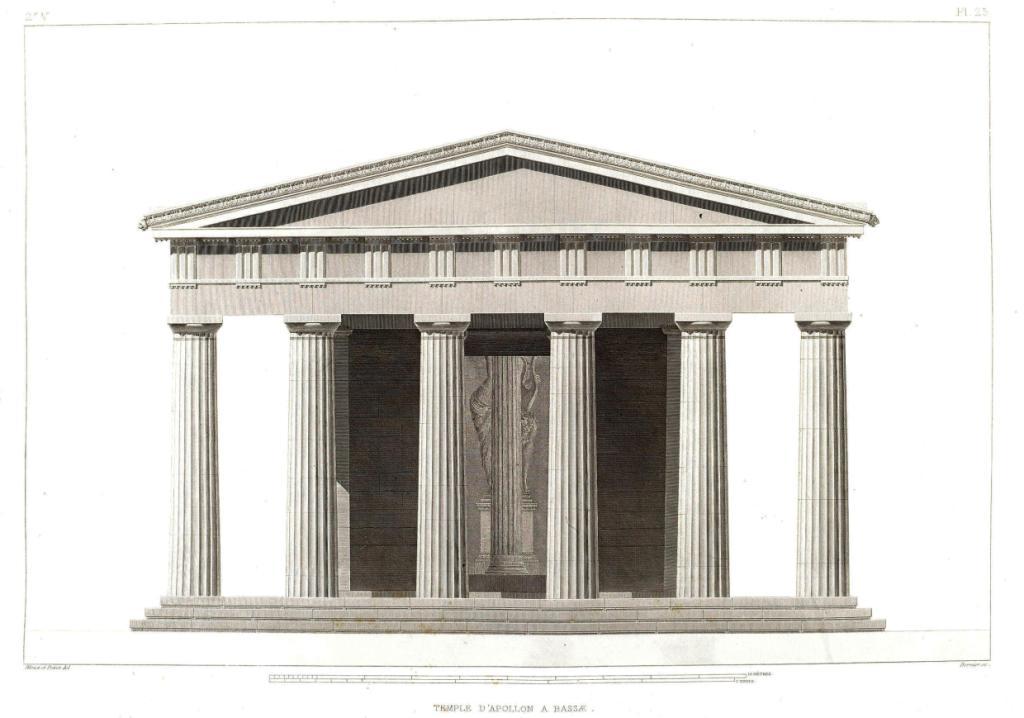

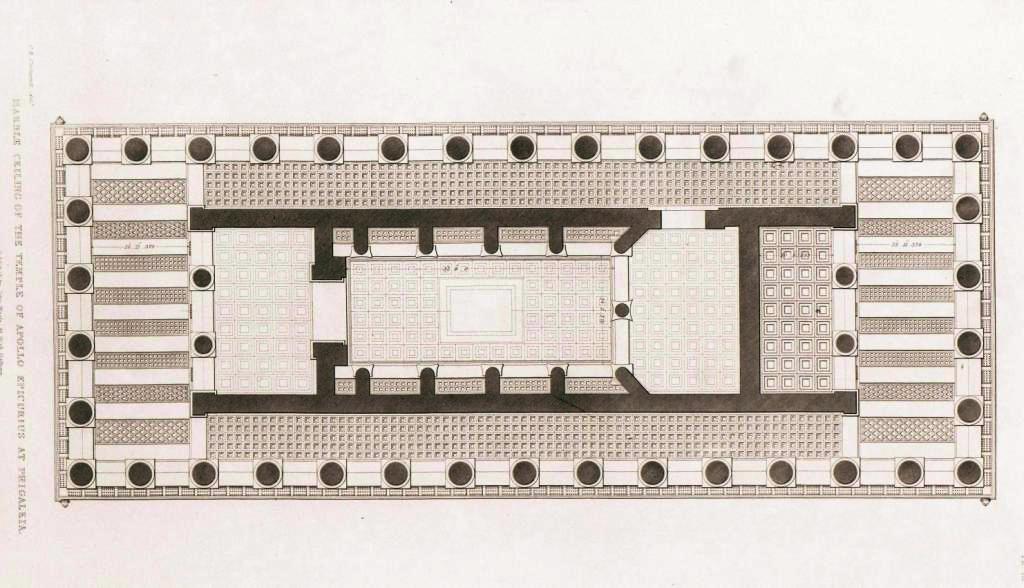

It is a Doric style temple, with peristyle (a colonnade around the cella), consisting of six Doric columns on the narrow sides and fifteen on the long sides, distyle in antis, with pronaos, cella, adyton and opisthodomos, with its elongated axis emphasized, where the wings of the short sides are twice as wide as that of the long sides.

“….. The floor plan of the temple (its tracery as it was called in antiquity) could be characterized as a “choreography” of contrasts as the long wings of standard width alternate with the short “wings” of twice the width, the spacious and richly decorated pronaos which is juxtaposed with the narrow and austere opisthodomos (rear cella), while the uniquely shaped cella is combined with a simple in architecture, small-scale, adyton …” *

The orientation of the temple

Structural materials – Quarries

Foundation – Crepidoma (Steps)

The colonnade (peristyle – ptero) of the temple

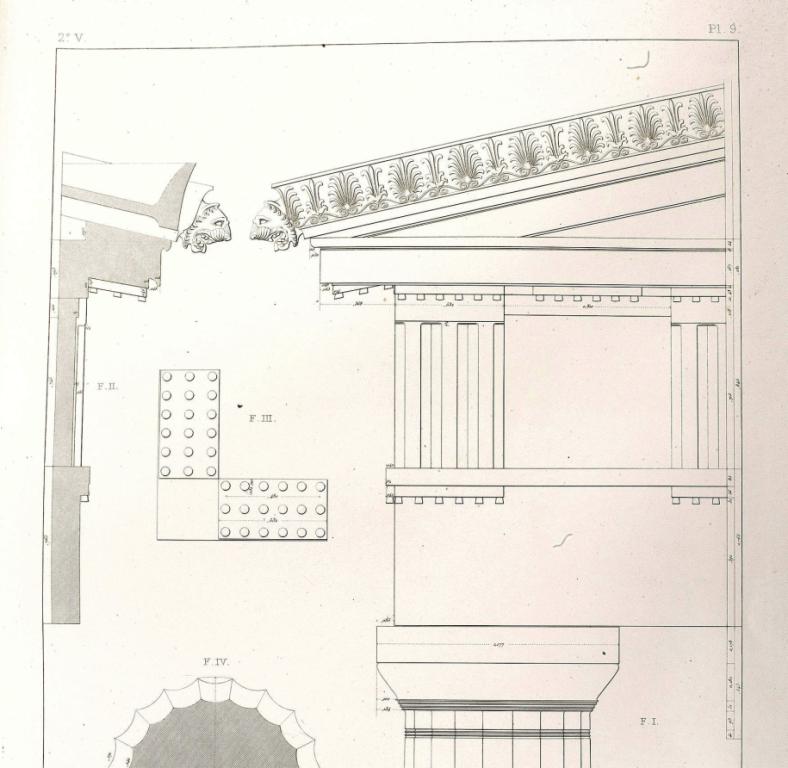

Entablature

Cella (Sekos – main temple)

Both in the pronaos and in the opisthodomos, above the pilasters and the intermediate columns, there was an entablature with an architrave and a doric frieze.

The frieze was formed by seven triglyphs and six metopes, which should have had relief representations, according to the model of the temple of Zeus in Olympia. This relief decoration must have been of great artistic value, as can be seen from the admittedly few fragments that were saved and are exhibited in the British Museum. According to Professor Brian Madigan, the subject depicted by the metopes of the pronaos was probably the return of Apollo to Olympus from the Hyperborean land, while the corresponding metopes of the opisthodomos depicted the abduction of the daughters of Leucippus, king of Messenia, by the Dioscuri.

The pronaos is deeper than the opisthodomos, while their ceilings had marble coffer. Between the pilasters and columns of the porch there were railings while a large door, 2.63m wide. it allowed communication with the cella.

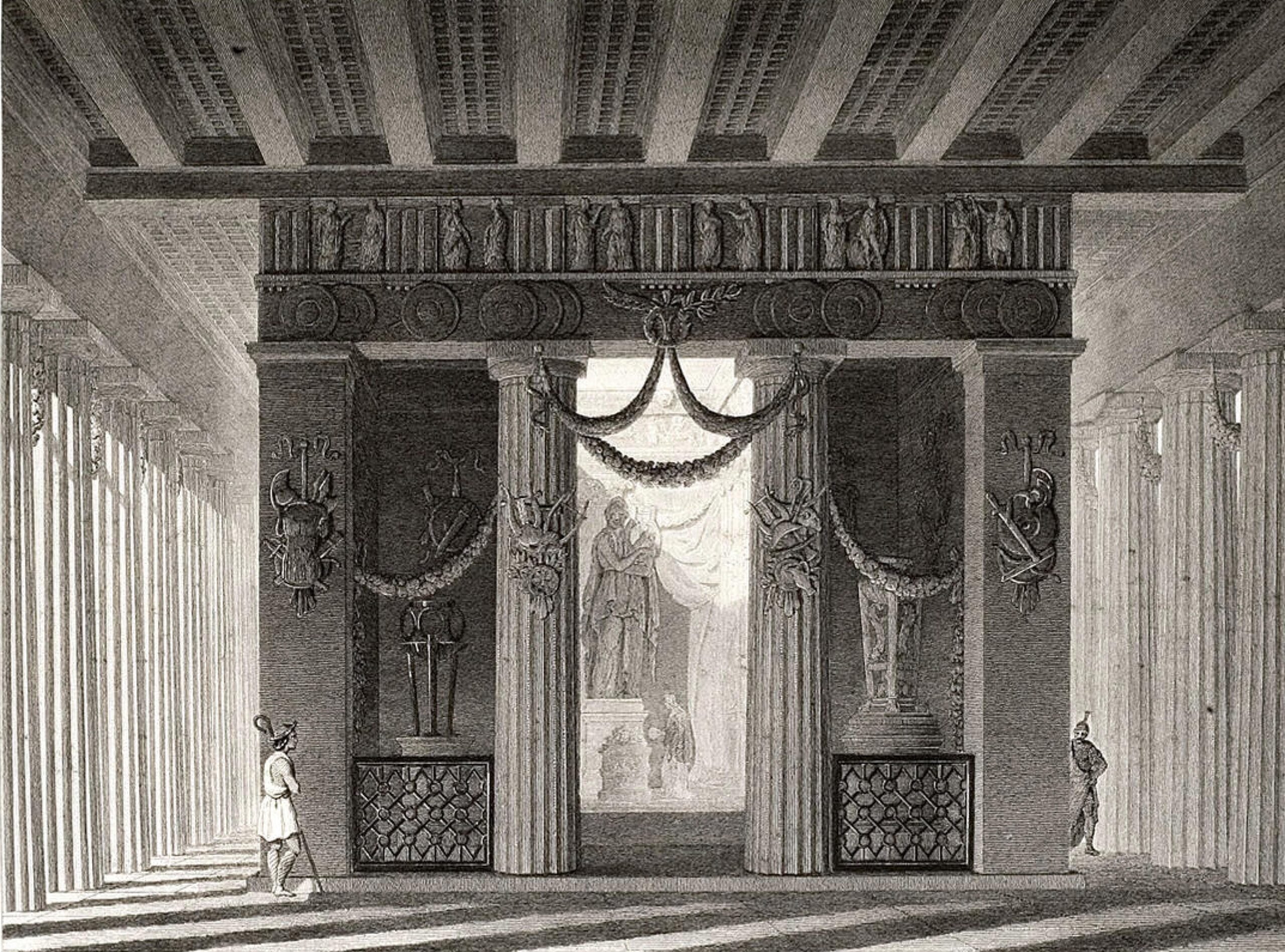

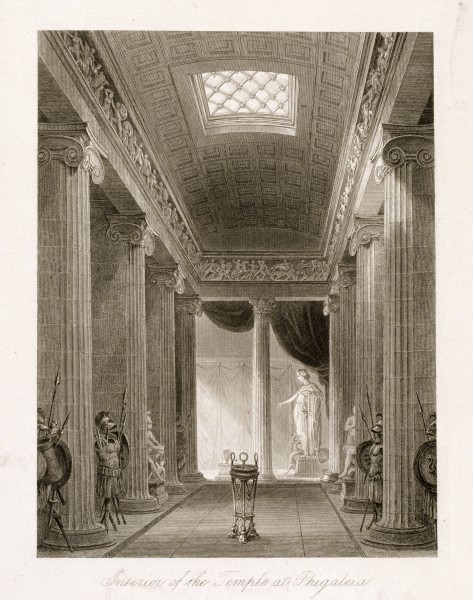

The interior of the cella

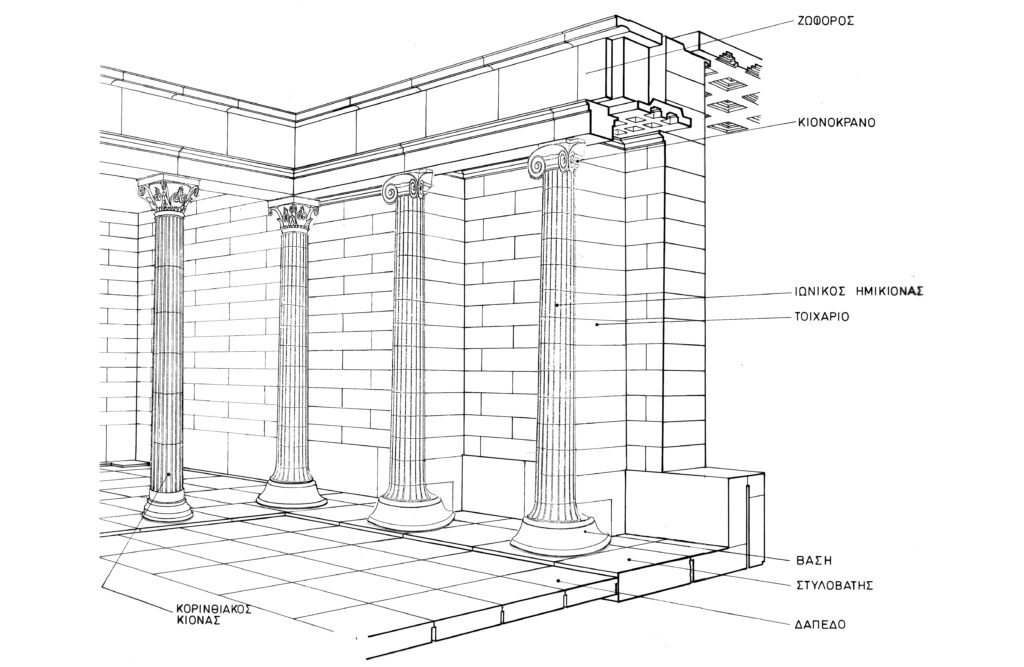

One of the most characteristic features of the monument is the interior arrangement of the cella. Instead of the expected tripartite structure, i.e. a P-shaped colonnade usually surrounded the cult statue, creating three aisles (corridors), in the cella of the temple of Epicurus Apollo there are five pairs of Ionic semi-columns connected vertically to the walls of the cella, with the exception of the southernmost pair joining the walls at an angle of 45 degrees. Spacious niches are thus formed along the walls, a structure that resembles the interior of the archaic temple of Hera in Olympia (600 BC). It is uncertain whether this choice was dictated by some cultic or religious tradition, in terms of spatial planning, however, the use of semi-columns instead of colonnades allowed for the best utilization of the comfortable and spacious interior corridor. If the typical structure of the cella of the classical era temples had been preferred, the central space would have been limited and narrow.

The adyton

Continuation of the cella but a distinct part of it is the adyton, an arrangement that finds a parallel in the archaic temple of Apollo at Delphi. For the first time, the opening (door) 1.91m wide, (smaller than that of the pronaos) appears on the eastern wall of the adyton. This opening corresponds to the tenth from north interval space between the columns of the peristyle.

The purpose of the adyton has not been fully interpreted, but it is thought to have had a cultic significance. It is hypothesized that every morning the sun’s rays entered through the door and illuminated the cult statue of the god or possibly an altar placed inside the adyton. In fact, the two lever holes near the transverse wall that separates the adyton from the cella, it is possible that they supported the pedestal of the cult statue.

The cult statue of Apollo

Many theories have been formulated by scholars about the cult statue, its form and where it was erected, even whether it existed.

Historical accounts are scanty and are limited to the testimony of Pausanias who saw a large bronze statue of the Epicurius Apollo 12 feet high in Megalopolis set on an impressive plinth. It had been brought there from Vasse when Megalopolis was founded, around 369 BC. in order to decorate the new city. In 1812, life-size marble fragments of hands and feet had come to light, in front of the Corinthian column. It is therefore possible that the statue that was brought to Megalopolis was the one that was placed in the adyton, opposite the eastern opening. Various drawings of scholars have survived, some of whom place it near the western wall, in the eastern corner of the adyton, in front of the Corinthian column, or even inside the cella.

Perhaps even when the original statue was moved to Megalopolis, the gap was filled by a new life-sized one that was made of wood but had marble edges (acrolithic).

The archaeologists Panagiotis Kavvadias and Nikolaos Gialouris distanced themselves quite a bit from the above theories, arguing, Kavvadias on one hand, that the bronze statue that Pausanias saw in Megalopolis stood somewhere in the surrounding area of the temple of Bassae and that there was only a cultic xoanon in the temple, and Gialouris on the other that the column itself was the non-figurative representation of the deity and there was no statue inside the temple. This view is based on ancient cults of pillar worship found in Arcadia (e.g. Tegea), where an architectural element (column, stylus or post) was worshiped instead of a cult statue of the respective deity.

Kavvadias’ view that perhaps the statue with its pedestal was placed outside the temple near the north-east corner is also supported by the scholar and restorer of the monument K. Papadopoulos, interpreting an elongated, particularly large boulder as the pedestal of a bronze statue ( or statues, due to its great length).

The corinthian capital

Between the last pair of semi-columns of the walls of the cella arranged diagonally and not vertically like the rest, there was a column topped by a Corinthian capital, the oldest known in ancient Greek architecture. Fragments of it are kept in the National Archaeological Museum. The column, together with the Ionic semi-columns (according to some scholars, also Corinthian) supported the architrave of the south wall of the cella which in turn carried the Ionic frieze.

The first drawing of the Corinthian capital was made by K. H. von Hallerstein (1811-1812), while the Estonian Otto Stackelberg, who supervised the 1812 research work in Bassae, reported :

«… The base of one column, the only one with a capital with carved leaves (apparently meaning the Corinthian capital) was no longer attached to the perimeter pilaster, but had been moved from its position. The capital was next to the column, in the cella, where there were also more Ionic capitals of semi-columns, scattered among the pieces of the larger coffered panels of the ceiling, which preserved clear traces of the painted decoration.…»

The capital’ s basket had one or two rows of thorn leaves at the bottom, from which sprouted shoots that went up to the abacus and formed the four corners. Between them was a pair of volutes crowned by an anthemium. At the top the capital ended in an abacus with a curvature in the center.

It is considered the oldest capital in Greek architecture, the existence of which eloquently demonstrates the innovative ideas and the willingness of the architect of the Temple of Epicurious Apollo to experiment, who does not hesitate to use a plant motif, the acanthus leaves, thus going outside the strict, traditional rendering framework of the stylized form of the colonnade, Doric and Ionic.

Unfortunately the first Corinthian capital in the history of architecture is not preserved today. However, the detailed drawings made by the scholars in 1812 somewhat fill the gap.

The scientific debate about the birth of the Corinthian style in Bassae and the interpretation of its differentiation from the rest of the capitals of the temple, Ionic and Doric, continues.

The roof of the Temple

The roof of the temple was pitched and covered by 17 rows of marble tiles of the Corinthian type.

The pediments on the two narrow sides were framed by a horizontal and vertical cornice, while at the back they had a wall, the drum.

According to some scholars, the pediments of the temple had sculptural decoration, which during Roman times was transferred to Rome, possibly together with other works that adorned the temple, according to the favorite habit of the Romans who wished to use them to decorate the buildings of their capital.

Perhaps the pediments were undecorated, as some scholars argue in an attempt to explain their shallow depth.

Subtitle for This Block

The roof of the Temple

Ch. R. Cockerell, The temples of Jupiter Panhellenius at Aegina and of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae near Phigaleia in Arcadia, London 1860

On the long sides of the temple, the covering tiles of the roof ended in flowered cornices, above the horizontal cornice.

Stone slabs with panels on their lower surface, i.e. carved decorative shapes, created the roof of the temple.

The fate of the temple until modern times.

As evidenced by repairs carried out during the Roman era to the roof tiles, the temple was in use at least until this time, when Pausanias visited it, that is in 174 AD.

Human intervention in the form of detaching the metal links of the building material for to used for other purposes and needs, but also the natural phenomena, sometimes at great intensity (earthquakes, extreme weather conditions) caused the collapse of the roof and the general deterioration of the monument .

Sixteen centuries of silence and oblivion passed after the visit of Pausanias in the 2nd century AD, until the age of enlightenment and European travelers, when the monument once again comes to the fore of history.

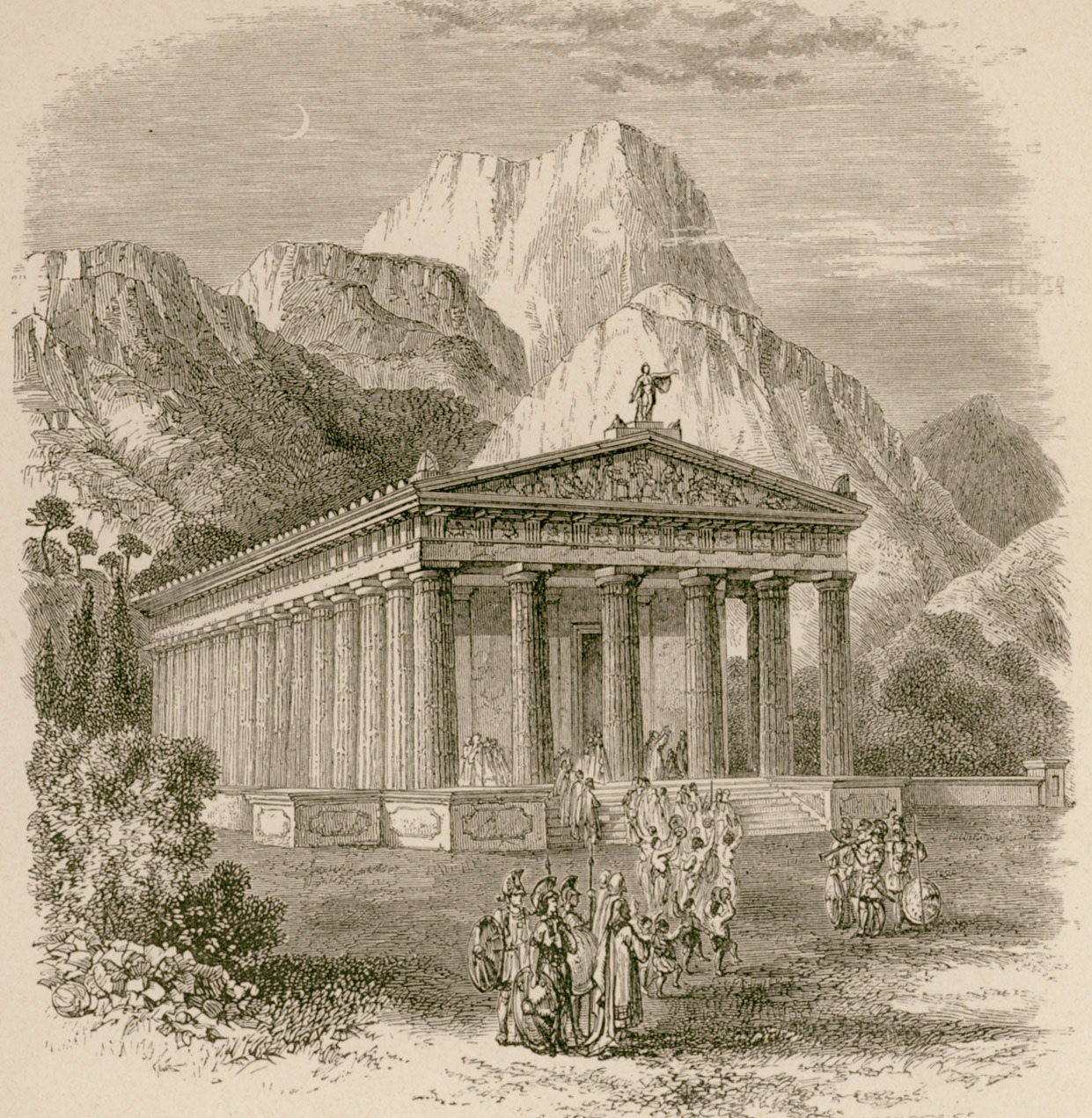

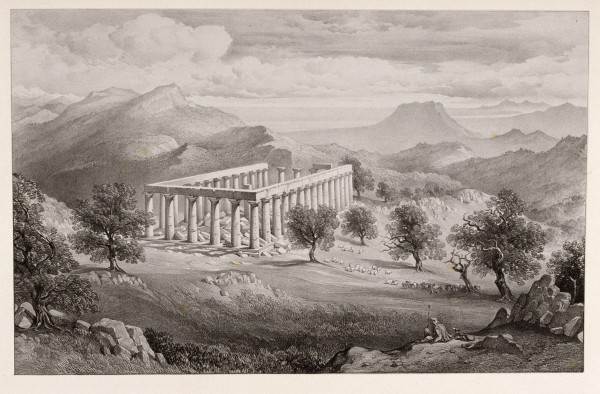

In many of the engravings of the 18th and 19th centuries, we can detect the romantic way in which European scholars and scientists depict the deserted, mysterious due to the frequent fog and bucolic landscape of the Bassae, but also their admiration for the eponymous monument, a worthy representative of the achievements of the classical spirit and culture of Greece.

Apollo Epicurius at Bassae

The bucolic landscape of Bassae with the temple as it was preserved until the 18th century

Ch. R. Cockerell, The temples of Jupiter Panhellenius at Aegina and of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae near Phigaleia in Arcadia, London 1860